We decided a while back that 2020 would be the year we’d leave Egypt. Andreas would take his retirement and I would find a new job that would take us somewhere new and different. Last fall I spent evenings and weekends searching for a library position on the recruiting circuit. I made some connections at a job fair in October followed by many hours researching schools, writing emails, and doing interviews. Finally, while on a family Christmas holiday in London, I carried a freshly signed contract into the post office in Maida Vale and mailed it back to my new school in Bangkok, Thailand.

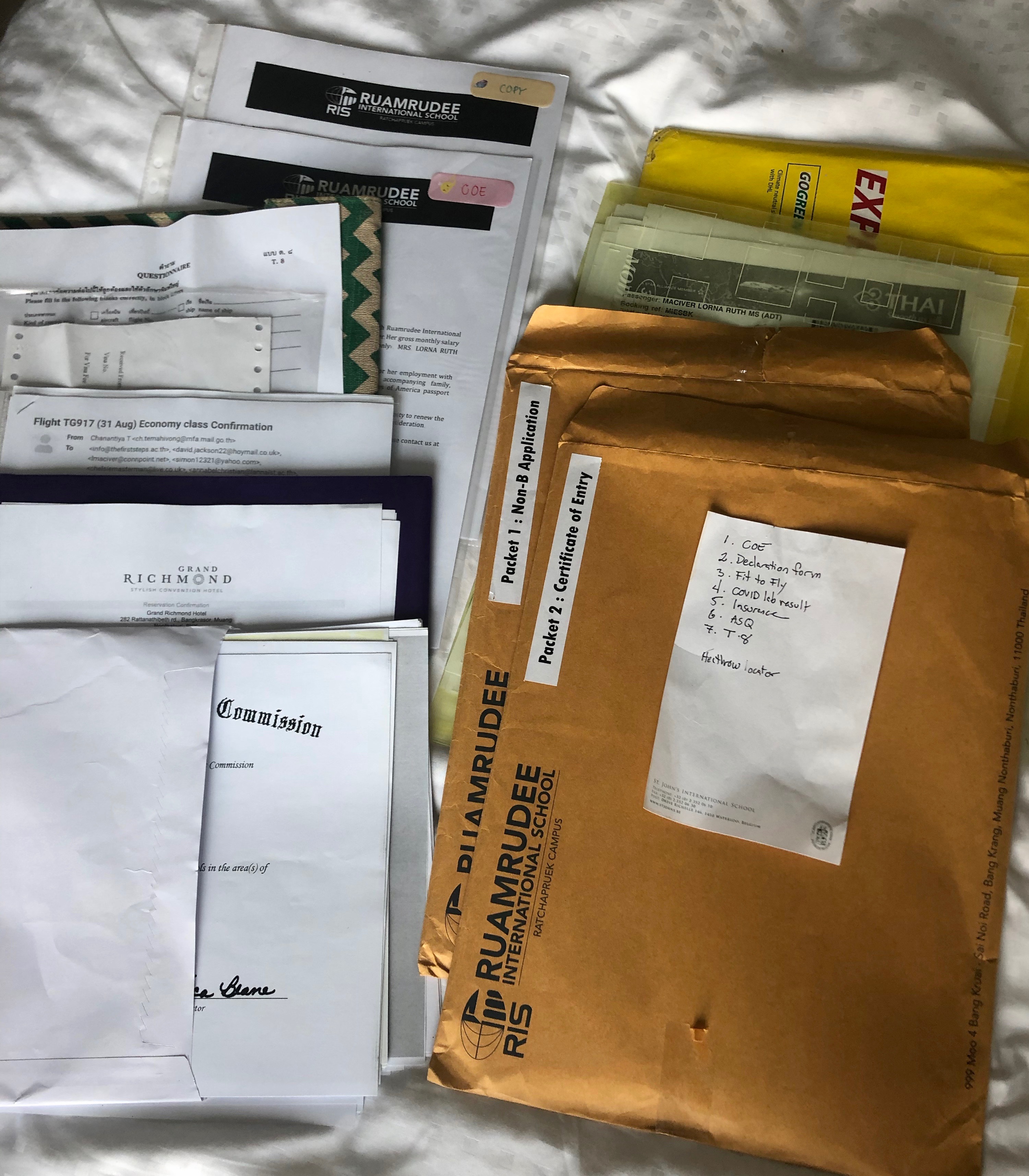

The instructions the school sent for obtaining a Thai work visa and teaching license for me and a dependent visa for Andreas were daunting, but we were very motivated by the prospect of moving to southeast Asia and joining a school I was excited about. Eight months seemed like plenty of time to gather everything. Of course no one knew then that a pandemic was on its way, nor how that would complicate the process.

Under normal circumstances, a move to Thailand for us would require assembling the following items for our visas. All legal documents have to be signed in blue ink only, all letters printed on official letterhead, and anything not in English translated and notarized:

1. Employer’s letter of request for visa

2. Employment certification from school

3. Proof of accreditation of Thai school (these first three items in both English and Thai, signed and stamped and sent to me DHL by my new school)

4. Original signed employment contract

5. Visa application forms for both me and my husband

6. Scans of passport main page and all pages with visas on them, for both me and my husband (for us, about 40 pages each)

7. New passport sized photos for me and my husband

8. Resume

9. Original teaching credential with seal

10. Official university diplomas for all degrees earned, with signatures and seals

11. Proof of accreditation of all universities attended (in my case, that’s three schools)

12. Official sealed transcripts from all universities attended, to be sent directly to Bangkok by the universities

13. Personalized confirmation letter signed and sealed by registrar of university where I obtained my highest degree, addressed to Teachers Council of Thailand, confirming awarding of degree

14. Letter from last job confirming two years of employment at that school

15. Official police clearance report from country of last employment with notarized English translation

16. Original marriage certificate

17. Notarized affidavit of name change (for Andreas, because our marriage certificate says Andrew)

18. Stamped bank statements for the preceding three months

19. Unexpired residence visas for current country of residence for both of us

About half of these are things I had in my files in Egypt or in the US (hurray for DHL and my daughter Alice). Some were forms to fill out myself or letters my current school could generate for me.

Others were trickier. We had to go to a photo shop for new pictures (#7). Not difficult as there is a Kodak store about a 20 minute walk from our apartment, but stressful, as COVID was raging in Cairo just then and we really didn’t want to go. Then I had to do it over because I had missed the instruction that said not to wear a white shirt.

Same thing with the stamped bank statements, #18. Didn’t enjoy having to sit in a crowded waiting room but we suited up with our masks and face shields and did it.

My undergraduate diploma from UC Berkeley, #10, had gone missing sometime between 1987 and 2020 and I had to order a new one. That wasn’t too bad as it was just an online form, but it took some serious sleuthing to find my old Cal ID number.

I had to submit a special request to the registrar at UCLA for #13 – a letter stating that yes I had earned my MA there on such and such a date because apparently the original diploma together with the sealed transcript weren’t quite enough evidence. Special requests have to be made in writing and paid for with a check (!) so again I had to enlist Alice in Oregon to do the legwork. Then because of COVID the process was delayed and it took seven weeks instead of the usual three making me quite nervous, but eventually the letter arrived in Bangkok.

My school in Egypt helped with the police clearance report, #15. A driver took me to a bleak little office at Cairo police headquarters to be fingerprinted, and a few days later the school picked up the finished document and had it translated and the translation verified.

#19, the Egyptian visa requirement, was a challenge. Our work visas had expired during the lockdown period when Egypt closed all the government offices. They stayed closed throughout Ramadan, finally reopening at the beginning of June. I don’t imagine the school was thrilled about sponsoring work visas for two departing employees with only two weeks of teaching left to complete, but they took us to the visa office and got us renewed through August 31. At the time that seemed more than sufficient, but as it turned out that was the day we left Egypt. But I am getting ahead of myself.

I don’t know how we lost our marriage certificate (#16) but we looked everywhere in Cairo and Alice looked everywhere in Medford and all anyone could find were photocopies. I had to order a new one. In California, where we got married, vital records are managed by county. At that time we lived in Alameda county and our wedding was in Berkeley, in the same county. I went online and discovered that in Alameda county you have to provide a notarized request or appear in person to get an official copy. Well…. the only place in Egypt you can get a legal US notary stamp is the US embassy. The embassy website informed me that notary services are suspended indefinitely due to COVID. I called them and they said nope, no emergency notary. It was an impossible situation. Then I looked again at the photocopy. I have no recollection of why, but for some reason we had applied for the marriage license and filed the certificate in Contra Costa County. I checked the county records office there and hallelujah, no notarization required. I ordered a copy sent to Alice and she added it to the DHL pile.

#17, the Andrew-Andreas name change, posed a problem again because of the notary requirement. After some investigation I located an American bar certified lawyer in Cairo who did notary services. An hour’s drive away and a ridiculous price, but the stamps and seal were worth it.

Whew. By the middle of June I had collected everything we needed for our visas. I had already bought our airline tickets back in May. We were to fly out on July 23, with our two cats Rosie and Mishmish in their reserved spots under the seats in front of us. Perfect timing as that was the day the lease on our apartment was up. Now I just had to get the import permits and some other documents for the cats and arrange for shipping our household goods to Bangkok. We also thought we’d ship a few things back to Medford, including my younger daughter’s belongings from when she left for university (and still more stuff that she brought back from the UK after she graduated).

Then our plans went awry. Part two tomorrow.